The Renaissance and the Wider World

Harriet and Leila (Y12) explore the fascinating connections created between Italy and the rest of the world during the Renaissance period .

The Renaissance was a period of immense cultural, economic and artistic change, originating in Italy during the 14th century. Translating as rebirth, or rinascimento in Italian, it was a time of transformation for Europe and for the world beyond, creating a place on the global stage for Italy. We have explored the connection that developed between Italy and the rest of the world. Firstly we will address the Renaissance and it’s impact on literature and secondly on trade, politics, and the economics of the time.

Literature Harriet (Y12)

The Renaissance was the first time Italian writers were producing most works in Italian, rather than Latin or French. Literature of the time is characterised by its adoption of Humanist philosophy (belief that we only have one life to live) and often, the inclusion of characters or stories from antiquity, inspiring some of Shakespeare’s historical plays, like Julius Caesar and showing a connection between medieval Italy and the classical world.

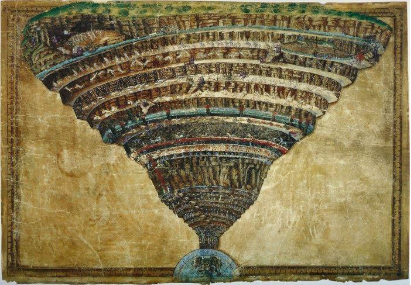

However, some works still focussed on Christianity, such as the very famous Divine Comedy (La Divina Commedia) by Dante. This revered piece of literature, describing a journey into the realms of the dead, served as inspiration for multiple works across the world (including numerous pieces of art). For example, John Milton, a revered English poet famous for his 1667 epic poem Paradise Lost, references Dante frequently in his work. In the 19th century, French novelist Honoré de Balzac wrote La Comédie humaine (The Human Comedy), generally considered to be an adaptation of Dante’s work. TS Eliot was heavily influenced by Dante too, for example in the structure of his first professionally published poem, The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock. Renaissance literature connected Italy to the rest of the world by providing literary inspiration for writers for centuries to come, creating connections not just through nations but also through time.

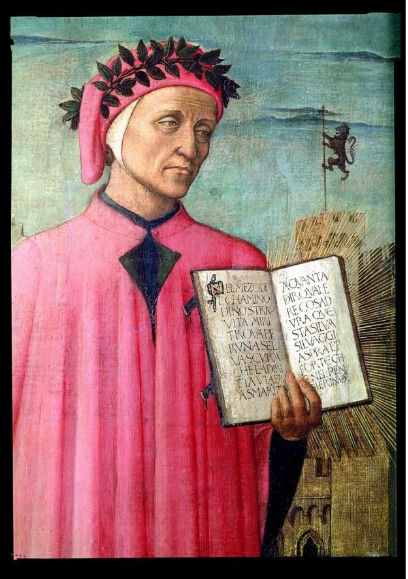

Dante Reading From the Divine Comedy (detail) Domenico di Michelino 1465

As well as changes in language (writing in Italian rather than French or Latin), the 13th century brought changes in themes for Italian poetry – for example the development of the Dolce Stile Nuovo focusses more on Platonic love, rather than romantic. This is exemplified in the works of Francesco Petrarch, a Renaissance Humanist who wrote poems to his friends. Poetry about romantic love, though, is almost constantly present in every cultural transformation, and so is also exemplified by Petrarch’s pieces. His most famous work from the time is a collection of love sonnets called the Canzoniere (‘songbook’ in English), dedicated to his great unrequited love, named as Laura. His works were translated into English by Thomas Wyatt which led to the development of the sonnet form in England, where famously Shakespeare used it extensively. Renaissance literature built connections between Italy and the rest of the world through the sharing of literary techniques and structures.

Another key example of a way Renaissance literature from Italy impacted the world is through its spread of new ideas: it established humanism as an alternative worldview to the Christianity that had pervaded the Middle Ages. It encouraged individual expression through the reworking and reviving of classical texts, and even offered new approaches to government and politics: Niccolò Machiavelli’s political writing, The Prince, presented a new, more realistic approach to political theory, which greatly influenced modern political thought. For example, Karl Marx, author of Das Kapital (1867), praised Machiavelli extensively for his ideas, calling his work Florentine Histories a ‘masterpiece’. Marx’s political theory went on to influence innumerable others, showing another example of a stretching connection between Italian Renaissance literature, and the rest of the world.

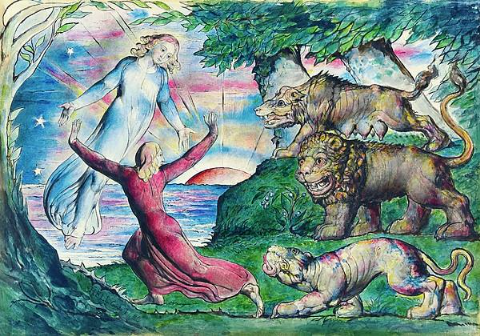

William Blake, Dante running from the Three Beasts 1824–7

Economics, politics and trade – Leila (Y12)

Durante il Rinascimento, l’Italia si trovava alla crocevia di Europa, Asia e del mondo Mediterraneo. Anche se era divisa in città-stato indipendenti come Firenze, Venezia, Milano e Genova, l’Italia divenne un centro di connessioni attraverso l’economia, il commercio e la politica. Questi legami non collegarono solo l’Italia al resto d’Europa, ma anche al mondo intero, rendendola un motore fondamentale di cambiamento culturale ed economico in questo periodo.

L’economia giocò un ruolo vitale in queste connessioni. Firenze, in particolare, si sviluppò come una potenza bancaria sotto famiglie come i Medici, che introdussero strumenti finanziari innovativi come il credito e le cambiali. I banchieri italiani concessero prestiti ai monarchi in Francia, Inghilterra e nei Paesi Bassi, integrando così l’Italia nella politica e nel commercio europei. La ricchezza generata da queste innovazioni finanziarie permise alle élite italiane di sostenere artisti, architetti e studiosi, le cui opere circolarono oltre i confini della penisola e contribuirono alla diffusione del Rinascimento in tutta Europa.

Il commercio creò un ulteriore livello di connessione globale. Le repubbliche marittime come Venezia e Genova dominarono il commercio mediterraneo, fungendo da intermediari tra l’Europa e l’Oriente. Esse importavano spezie, sete e altri beni di lusso dall’Asia, spesso attraverso mercanti ottomani e arabi, e li distribuivano nei mercati europei. Queste città-stato furono anche luoghi di scambio culturale, trasmettendo conoscenze di matematica, astronomia e medicina dal mondo islamico all’Europa. Navigatori italiani portarono questo spirito di esplorazione ancora più lontano: Cristoforo Colombo, nato a Genova, e Giovanni Caboto, di Venezia, aprirono nuove rotte commerciali verso l’Occidente navigando sotto bandiere straniere. In questo modo, le competenze e le reti italiane collegarono il Mediterraneo con le Americhe.

La politica integrò ulteriormente l’Italia con il resto del mondo. La rivalità tra città-stato favorì lo sviluppo della diplomazia, e i diplomatici italiani furono i primi a usare ambasciatori permanenti, un sistema poi adottato in tutta Europa. Roma, come sede del Papato, collegava l’Italia al mondo cattolico, influenzando i regni europei e persino le prime imprese coloniali oltreoceano.

Tuttavia, la centralità globale dell’Italia svanì con il tempo. Con l’ascesa delle potenze atlantiche come Spagna, Portogallo, Inghilterra e più tardi Francia, le rotte commerciali si spostarono lontano dal Mediterraneo. Le città-stato italiane persero il loro ruolo centrale nella finanza, nell’esplorazione e nel commercio. Nel XVII secolo, l’Italia era ormai più un campo di battaglia per gli imperi stranieri che un protagonista della scena mondiale. Nei secoli successivi, la penisola rimase politicamente frammentata e spesso soggetta al dominio di potenze esterne, fino all’unificazione nell’Ottocento.

Oggi, l’Italia continua a essere un paese influente soprattutto nella cultura, nella moda, nell’arte e nel turismo, ma non domina più l’economia o la politica internazionale come un tempo. Questo contrasto tra la leadership globale dell’Italia rinascimentale e il suo ruolo più ridotto nel presente mette in evidenza sia la grandezza delle conquiste del passato, sia come i centri di potere nel mondo cambino nel tempo. L’esperienza dell’Italia dimostra come l’innovazione, la ricchezza e le idee possano dare a una nazione un ruolo centrale nella storia, ma anche come tali posizioni possano svanire quando gli equilibri economici e politici globali si spostano altrove.

(During the Renaissance, Italy stood at the crossroads of Europe, Asia, and the Mediterranean world. Although it was divided into independent city-states such as Florence, Venice, Milan, and Genoa, Italy became a centre of connections through economics, trade, and politics. These links not only tied Italy to the rest of Europe but also to the wider world, making it a key driver of cultural and economic change during this period.

Economics played a vital role in these connections. Florence, in particular, developed into a banking powerhouse under families such as the Medici, who introduced innovative financial tools like credit and bills of exchange. Italian bankers granted loans to monarchs in France, England, and the Low Countries, thus weaving Italy into European politics and commerce. The wealth generated by these financial innovations allowed Italian elites to support artists, architects, and scholars, whose works spread beyond the peninsula and contributed to the wider European Renaissance.

Trade created another layer of global connection. Maritime republics such as Venice and Genoa dominated Mediterranean commerce, acting as intermediaries between Europe and the East. They imported spices, silks, and other luxury goods from Asia, often through Ottoman and Arab merchants, and distributed them in European markets. These city-states were also centres of cultural exchange, transmitting knowledge of mathematics, astronomy, and medicine from the Islamic world to Europe. Italian navigators carried this spirit of exploration even further: Christopher Columbus, born in Genoa, and John Cabot, from Venice, opened new trade routes westward under foreign flags. In this way, Italian expertise and networks linked the Mediterranean with the Americas.

Politics further integrated Italy with the rest of the world. Rivalries among the city-states encouraged the development of diplomacy, and Italian diplomats were the first to use permanent ambassadors, a system later adopted across Europe. Rome, as the seat of the Papacy, connected Italy to the Catholic world, influencing European kingdoms and even the early colonial ventures overseas.

However, Italy’s global centrality eventually faded. With the rise of the Atlantic powers such as Spain, Portugal, England, and later France, trade routes shifted away from the Mediterranean. The Italian city-states lost their central role in finance, exploration, and commerce. By the seventeenth century, Italy had become more of a battlefield for foreign empires than a driver of world affairs. In the following centuries, the peninsula remained politically fragmented and often under the control of external powers, until its unification in the nineteenth century.

Today, Italy continues to be influential, especially in culture, fashion, art, and tourism, but it no longer dominates the global economy or politics as it once did. This contrast between Renaissance Italy’s global leadership and its more limited role today highlights both the greatness of its past achievements and the ways in which centres of world power shift over time. Italy’s experience shows how innovation, wealth, and ideas can give a nation a central place in history, but also how such positions can fade when global economic and political balances move elsewhere.

References

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Divine_Comedy_in_popular_culture

https://fiveable.me/the-renaissance/unit-10

Francesco Petrarch engraving

Dante Reading From the Divine Comedy (detail) Domenico di Michelino 1465